Isn’t ISIS Militarism the Historical Norm for Islam?

It’s commonplace to talk about Islam as a “religion of peace” these days, suggesting that ISIS is surely an unrepresentative historical aberration. True enough if the rank-and-file of any population can be said to be more focused on day-to-day comforts and routine survival. But can’t the same be said of the peoples of Germany and Japan during World War II?

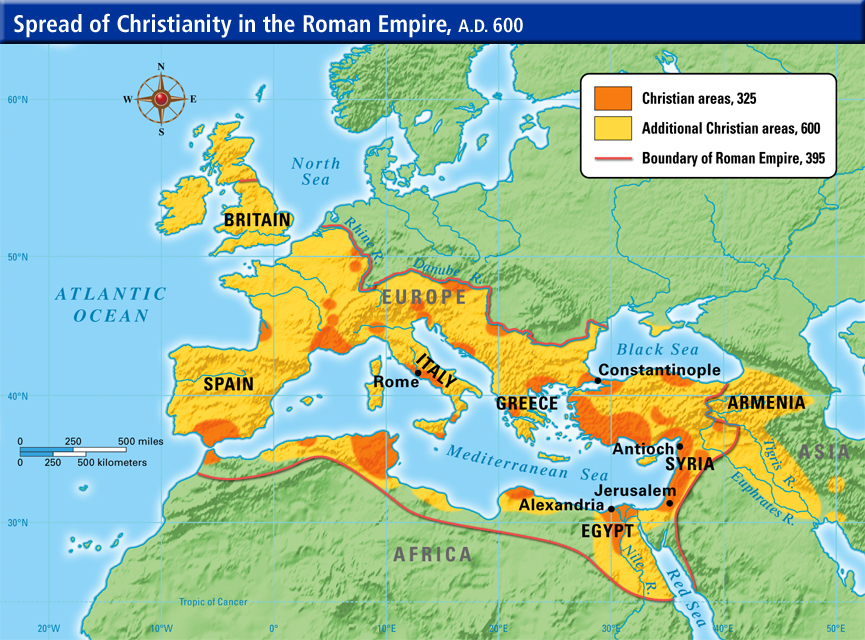

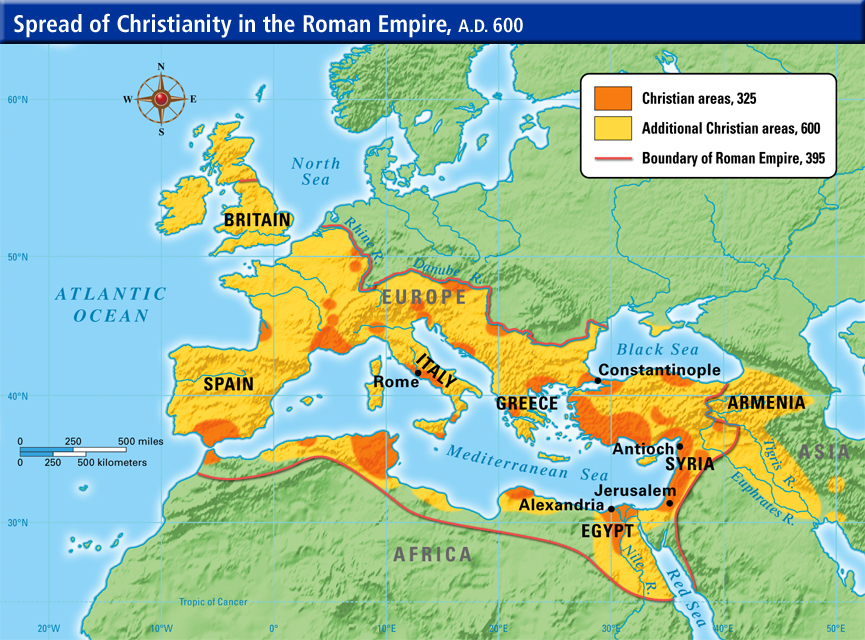

In many ways ISIS militarism is the historical norm. As my “Vanished Christian Worlds Once Thrived Before World War I” warns, we can “Look at any map of Christendom before Islam–and then after–to discover what Christians have lost by not confronting baleful force with greater force.”

Right out of the starting blocks, Islam’s success as a religion has sometimes been directly proportional to its willingness to be led by a ruthless, but determined militaristic minority. Or has its use of military force paralleled the decline of the Middle East, only recently revived by the “luck” of oil discovery? Have more converts been won over by a well-contemplated perusal of religious doctrine or by the more compelling policy of “put to the sword all those who won’t accept conversion”?

Even so, didn’t the Emperor Constantine rely on some of these tactics to give a struggling Christianity just the boost that it needed to align itself with the political muscle of the Roman Empire, resulting in the establishment of eastern Orthodox Church in Constantinople? Was Constantine influenced by Jesus’s own words in Luke 19:27: “But those enemies of mine who did not want me to be king over them–bring them here and kill them in front of me”?

What would Constantine have said to the citizens of his beloved Constantinople when it fell to ISIS-like Islamic armies in 1453, just 64 years before the beginning of the Reformation in 1517? Is peace simply the convenient posture of those who hold the upper-hand, leaving unmasked militarism to the desperate underdog?