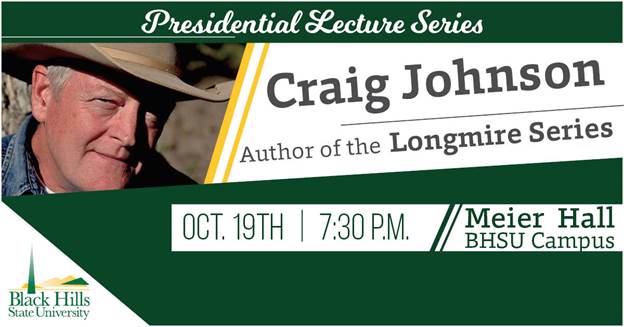

Listening to Longmire novelist Craig Johnson at Black Hills State University last Thursday evening reminded me that it is still cogent to “Base Freedom and Equality on Land Mass, Not Head Count.” Liberals and immigrants may be bottled up in big cities—along with big media, government, and colleges—but they will never represent rural and small-town America that the US was founded on:

“The presidential election of November 2016 also reminded us that the greater land mass of the United States of America is overwhelmingly on the political right. Most counties and rural areas went for Trump, even in liberal strongholds like the Northeast.” President Trump taught America that the “GOP Has Finally Found Its Big Tent” beyond establishment politicians seeking to protect their re-election prospects.

“The presidential election of November 2016 also reminded us that the greater land mass of the United States of America is overwhelmingly on the political right. Most counties and rural areas went for Trump, even in liberal strongholds like the Northeast.” President Trump taught America that the “GOP Has Finally Found Its Big Tent” beyond establishment politicians seeking to protect their re-election prospects.

Absaroka Sheriff Walt Longmire, though based on a fictional Wyoming county, is central to novelist Craig Johnson’s zeitgeist or defining spirit. Counties are counties, we might further add. Leave New York City or Boston and a few other urban enclaves, and the rest of New York and Massachusetts share a commonality with counties across America. They’re conservative places, from rough-and-tumble rustbelt neighborhoods to farms and ranches everywhere.

Absaroka Sheriff Walt Longmire, though based on a fictional Wyoming county, is central to novelist Craig Johnson’s zeitgeist or defining spirit. Counties are counties, we might further add. Leave New York City or Boston and a few other urban enclaves, and the rest of New York and Massachusetts share a commonality with counties across America. They’re conservative places, from rough-and-tumble rustbelt neighborhoods to farms and ranches everywhere.

In his BHSU lecture, Johnson jokingly quipped that the only real piece of “fiction” in his novels is the legal disclaimer at the beginning. Novels are largely based on observed social truths and human nature, he says.

Johnson’s first novel Cold Dish lets us know that know that beauty sometimes must make use of the imagination: “Scientists say there is a noise that snowflakes make when they land on water, like the wail of a coyote; the sound reaches a climax and then fades away, all in about one ten-thousandth of a second.” He learned this on his ranch near Ucross, Wyoming, population 25.

Absaroka County is an important political probe as well, an antidote to top-down, big money political machines. “I thought about how we tilled and cultivated the land, planted trees on it, fenced it, built houses on it, and did everything we could to hold off the eternity of distance—anything to give the landscape some sort of human scale. No matter what we did to try and form the West, however, the West inevitably formed us instead,” as he explains in The Dark Horse. The land itself imbues us with all the values worth having, not the other way around.

Lawyers and establishment politicians seem to live-in abstracted and artificial worlds, ones where legalese is the language spoken. But Netflix viewers of the Longmire series (and readers of The Dark Horse) know that Absaroka County, Wyoming, is actually more real and recognizable: “Most people go through their lives believing in things that they never have much contact with – the police, lawyers, judges, and courts. They have an unstated belief in the system; that it’ll be impartial, fair and just. But then there’s the moment when it comes to them that the police, the courtroom, and the laws themselves are just human, vulnerable to the same shortcomings as all of us, that they’re a mirror of who we are, and that’s the heartbreaking dichotomy of it all – that the more contact you have with the law, the less belief you have.”

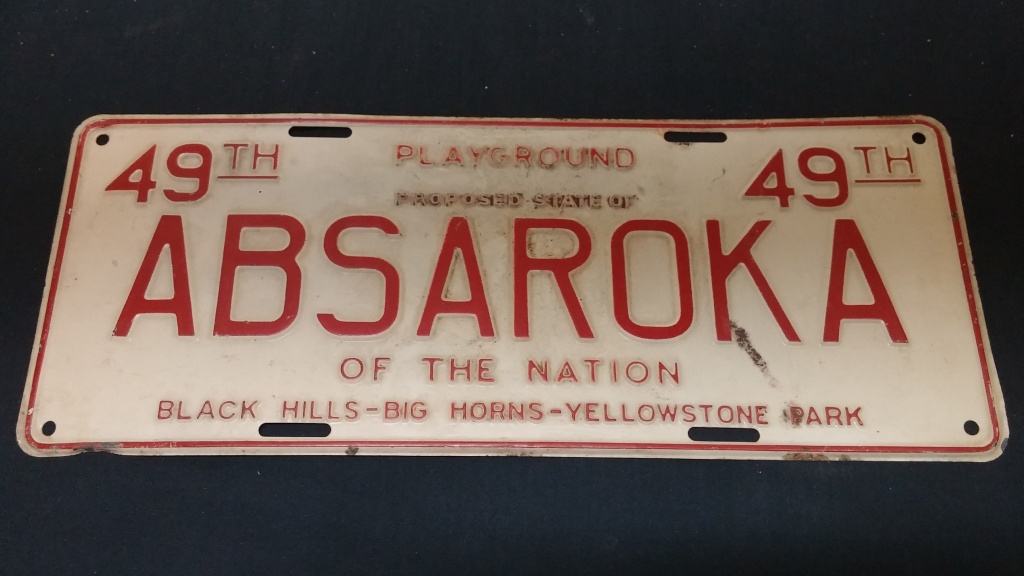

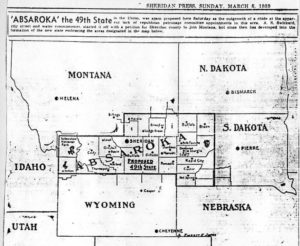

The BHSU campus was a fitting place to hear more about Absaroka County for another reason as well, because both Spearfish and Rapid City once held an even closer identity with Longmire’s county, as noted above: “The Absaroka statehood movement involving parts of South Dakota, Wyoming and Montana during the 1930s fizzled out when World War II began. They too would probably have had little success with purely parliamentary maneuvers, and federal lands wouldn’t have been relinquished without bloodshed.”

The BHSU campus was a fitting place to hear more about Absaroka County for another reason as well, because both Spearfish and Rapid City once held an even closer identity with Longmire’s county, as noted above: “The Absaroka statehood movement involving parts of South Dakota, Wyoming and Montana during the 1930s fizzled out when World War II began. They too would probably have had little success with purely parliamentary maneuvers, and federal lands wouldn’t have been relinquished without bloodshed.”